Make No Law Actually Means Make No Law

Mahmoud Khalil, the First Amendment and immigrants who dare to talk

A few years ago I wrote a law review article called When Immigrants Speak, about immigrant free speech rights. That’s a subject in the news right now owing to the Trump Administration’s detention, attempted deportation and general repression of Mahmoud Khalil because he had the chutzpah to express his opinions in public while inside the United States of America.

I was only a little bit surprised to see my article quoted out of context in a blog post that supports the repression of Mr. Khalil’s free speech. The blog post is by Mr. George Fishman, and was published by an organization with eugenicist and white nationalist origins, known as the Center for Immigration Studies. It argued that “aliens do not have the same First Amendment rights as American citizens.” I would like to respond.

I want to take Mr. Fishman’s views seriously. Thus, before addressing the substance of what he argued and how he quoted my work, I first checked his professional biography on the Center’s website. I had to do this because Mr. Fishman says that only some people have the full right to express themselves in this country. And yet, I was surprised to find no explicit statement there indicating whether Mr. Fishman is a U.S. citizen, or even if he is in this country legally. According to Mr. Fishman’s argument, does he even have the right to express himself through writing and publishing on matters of public concern?

Of course, I quickly realized my folly. My own professional biography also says nothing about my citizenship or immigration status. Now, I could send Mr. Fishman a copy of my birth certificate, so that he would not send DHS to visit me. But upon further research, I worried that even that might not be enough. You see, the Center for Immigration Studies rejects birthright citizenship.

So, while I want to take Mr. Fishman’s argument as seriously as possible, I think I am going to have revert to my own usual first principle on these matters. That is, I believe that Mr. Fishman, Mr. Khalil, and all people in the United States, enjoy full freedom of speech. To require the checking of papers before requiring the government to respect our mutual freedom of expression would be absurd. It would invite government harassment of dissenters. Publish a letter to the editor critical of the President, and you get a knock on the door checking on whether you have proof of citizenship.

No. As the Supreme Court wrote in the Citizens United decision, “restrictions distinguishing among different speakers, allowing speech by some but not others” offends the First Amendment. I don’t need to know Mr. Fishman’s citizenship status to know that he has every right to say what he said. In fact, no one really has freedom of speech unless we all have freedom of speech.

Thus, as a court might say, we proceed to the merits.

Undocumented Immigrants and the Selective Prosecution Problem

Mr. Fishman quoted two sentences of When Immigrants Speak:

The trouble with this is that I was writing primarily about a somewhat different problem than the one presented by the Mahmoud Khalil case.

To explain, forget for a brief moment that we are talking about immigration. Instead, imagine that you live in a small town. Now also imagine, hypothetically, that you are a person who sometimes drives a few miles over the speed limit. Imagine, that you’ve been doing this as long as you’ve had a driver’s license, and so do many other people, but the local police don’t usually pull anyone over unless they violate the speed limit by a lot. Not just for driving 38 in a 35 MPH zone. Now, imagine that you’ve just published an op-ed in the local paper critical of the mayor. And now, suddenly, you are getting pulled over by the cops all the time, and ticketed for going just 1, 2, or 3 miles per hour over the speed limit.

This is alarming, right? It seems like you’re being punished for criticizing the government, right? And yet: It is illegal to drive just one MPH too fast, so in a narrow sense you’re guilty, and the police aren’t wrong. That’s a problem under the First Amendment, but it’s not as straightforward as the government just explicitly throwing someone in jail for criticizing the mayor.

In normal free speech law, we do have a tool to address this problem. It’s the defense of selective or discriminatory prosecution. It’s not an easy road. But theoretically, even if you are guilty of violating the speed limit, you could defend yourself if you could prove that the police were selectively enforcing the law to discriminate against you for your constitutionally protected speech.

Now back to immigration.

Undocumented immigrants are extremely vulnerable to selective enforcement by the Department of Homeland Security. Basically, any undocumented immigrant is prima facie deportable. But, what if DHS singles out an undocumented immigrant for deportation because she engages in political speech?

This has happened. The point of my article was that the Supreme Court has sent conflicting signals about if and how undocumented immigrant activists can defend themselves from this situation. Making matters worse, the Department of Justice has actually been trying for awhile to argue in court that undocumented immigrants do not have First Amendment protection. That’s wrong, and the courts have not endorsed that position. But the courts have created an unfortunate muddle.

The Supreme Court has definitely left undocumented immigrants far more unprotected than they should be. In that respect, Mr. Fishman and I have some agreement about the state of the law — though not on every nuance, and certainly not on what the correct understanding of the First Amendment should be.

I would recommend reading this post by my colleague Alina Das. Like my law review article, she explains that despite allowing an alarming level of confusion about immigrant free speech rights, the Supreme Court has left the door open for undocumented immigrants to claim “outrageous” selective enforcement. However, all of this - including the quote from my article — is really about a different and harder problem.

Here is why: Mahmoud Khalil is not undocumented. His case is not about selective enforcement.

The Mahmoud Khalil Case Is Simpler

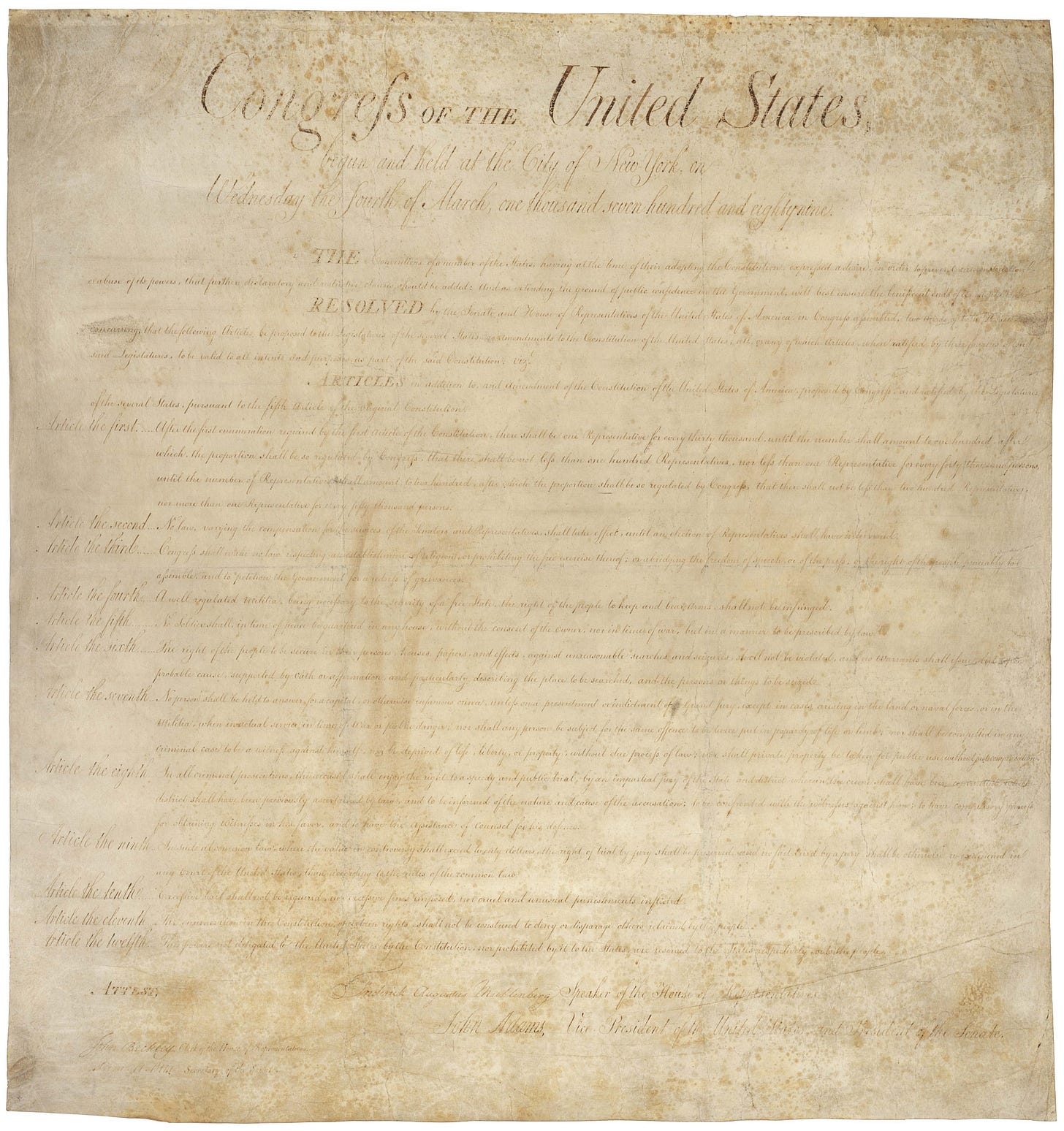

Courts like to say that text matters, so let’s read the text of the First Amendment:

“Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech.”

Mr. Khalil is a lawful permanent resident who has not been convicted of any deportable crime. The reason the Trump Administration claims he is deportable is explicitly because of his political activities. They are relying on a rarely used provision of the Immigration and Nationality Act:

An alien whose presence or activities in the United States the Secretary of State has reasonable ground to believe would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States [is deportable].

There’s not a lot of caselaw on this provision because the government has not tried to use it much. Maybe because it is subject to some obvious constitutional objections, even without touching on the First Amendment. In one of the rare cases where this provision was invoked, a federal district court said that it violates the right to due process to allow someone to be deported based on “the unfettered discretion of the Secretary of State and without any meaningful opportunity to be heard.” (The judge who wrote that happened to be Donald Trump’s sister. However, the decision was overruled on jurisdictional grounds, leaving even less legal clarity.)

The government’s case against Mr. Khalil is that he is deportable because one government official has decided that his activities — which would be clearly protected by the First Amendment for a citizen — are bad for U.S. foreign policy. That is basically the same as saying a newspaper cannot write an editorial criticizing U.S. foreign policy because of the author’s citizenship status. It is an abridgment of the freedom of speech.

If the First Amendment were written differently — if it said that Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech for citizens, then Mr. Fishman would have a good case to make. But that’s not what the Amendment says. It says make no law abridging the freedom of speech. Full stop. Freedom of speech for all.

For the record, I made this exact argument on page 1248 of my article, which is why I’m annoyed at being quoted out of context. But I concede that he has a right to quote me out of context.

The more important issue is the Constitution. Make no law means make no law. The problem in the Mahmoud Khalil case is that Congress made such a law, and the government is trying to use it explicitly to abridge freedom of speech.

That’s unconstitutional.

PS Elsewhere on t'internet, I am occasionally active on a discussion forum, where many people are of a right-wing persuasion. Some even hold very right-wing views. And occasionally the discussion touches the ECHR - often in connection with refugees and asylum seekers - and then some of my co-conversationists suggest that Brexit was not sufficient and that we (=GB) should leave the ECHR.

They argue that the ECHR protects [insert unpopular group] and they are right. These awful people are protected. But it's only BECAUSE the awful people are protected that we can be sure that WE will be protected should the situation arise: If they can get away with being beastly to those people, what's going to stop them being beastly to me?

I am European. In most of Europe we have the ECHR, the European Convention of Human Rights, which is explicit that the rights are there for all humans. ALL humans. Including people who have committed crimes and people who hold the most godawful views. ALL humans. Everyone.

I am glad that we have the ECHR.